Interviewed by Kristi Pinderi

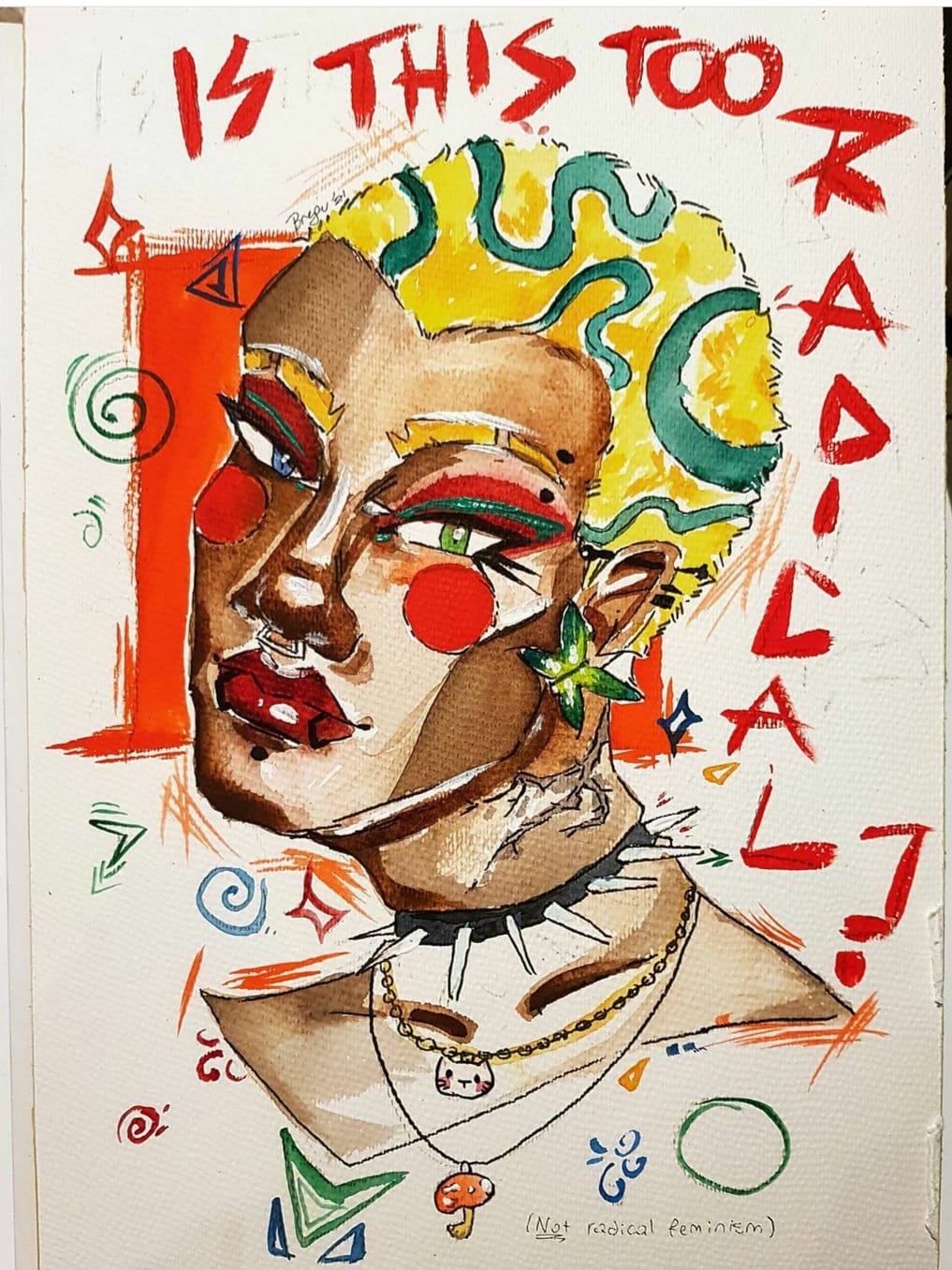

Ema Bregu’s exhibition opened at the “Public House” – a much needed oasis of feminism in Tirana – questions gender roles, beauty standards, and the social construct of “normal” based on the heteronormativity that rejects the notion that gender, as well as sexuality, may be fluid instead of binary.

In other words, this exhibition of Ema Bregu, 16, entitled “My body as a political subject” brings in Albania a core concept of the second wave of feminism. It positions the body – that has historically been a site of oppression and of exertion of power, into a new position of power, because anything – including our bodies – that is constantly under surveillance has in turn the potential to counteract, to resist, and to become an agent of change.

“My art is a form of resistance in its own way,” says Ema, who then adds: “My hope is that my art can be an inspiration and may be help to open discussions and debates on self-acceptance, challenging fixed social norms and standards, challenging beauty standards and allow for a more open society.”

We talk in this interview about the Albanian youth, about the fluidity of gender, we comment Judith Butler’s concept about gender being performative, we then discuss about the future, about a society that has based its expectations and norms on heteronormativity and how that impacts the voiceless and unrepresented people.

As such this may well be a rare opportunity in an Albanian media to discuss some essential notions of the queer theory, feminism and postmodernism.

Kristi: Ema, I was so happy and impressed when I saw the news about your exhibition. I was impressed that one can see in Albania young people like you who beautifully articulate with words and art some important feminist and postmodernist concepts like the body politics and how bodies have historically been sites of oppression and exertion of control (by state, other social institutions and social forces). Why did you choose that theme? What drove you there and how would you want people to see your work?

Ema: I chose that theme because it covers topics that should be discussed more openly with young people, especially in the context of a patriarchal and heteronormative society, like the Albanian society. This topic has been a personal concern and I have seen many friends that also struggled with things like self acceptance or beauty standards and so I wanted to present these feelings in a more subjective and distinctive way.

I want people to interpret my work as if it is their own. I want the audience to personally resonate with the image I put out despite what my personal theme may have been. This because I feel it is important that art is shared and art is comforting. I noticed this difference in perception of my works by the audience in my second exhibition. I was first nervous to share so much of my personal world with a wide audience, but when I saw the impact that it made, how young audiences resonated and found themselves in my work, I found peace with it.

Kristi: How did your art journey start? How did Ema discover the painting?

Ema: Art has always been part of my life, whether at school, at my art course, or at home. I have always been able to express myself through colours, and throughout my art journey, I discovered how meaningful art can be for other people too. Moreover, I realized that my work can be personal or shared. Discovering painting and new techniques was a journey of discovering myself through the difficult periods that I‘ve been going through as a teenager, especially after the recent earthquake in Albania, and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Painting has thus been a way for me to reveal my inner thoughts, emotions, opinions, in moments when it was difficult to verbalise them.

Kristi: Going back to body, politics, identity, power and resistance. Some people and scholars argue that power dynamics are not linear, people are not always on the ending side of the power, that they could shape it too, making power dynamics quite fluid. Within this fascinating dynamic people can also resist and counteract. Is your art a form of resistance?

Ema: I would say that my art is a form of resistance in its own way. I especially focus on challenging and subverting expectations in my art, for example, in ‘My body as a political subject’ exhibition, I covered many images that one would not perceive as “standard”, like representing different shaped bodies, beauty standards, sexism and fluid gender identities. I did this not only as a form of challenge, but to also represent everyday people, who are normal and common in our daily lives, yet are often overshadowed by the public’s obsession to represent the majority.

My hope is that my art can be an inspiration and may encourage open discussions about self-acceptance, challenging social constructed norms and standards, challenging socially constructed beauty standards, and making space for a more open society. And, yes, that may sound a bit aspirational and pretentious, but I do believe that young people especially have the potential to bring change and to deconstruct the ‘standard norm’ in order to open people’s minds and create an overall safer environment.

Kristi: It seems to me that portraits are an important form of your expression. I also see gender expression being potentially an important theme of your art, am I right?

Ema: Yes, gender expression is one of my main themes. Many paintings cover gender expression, whether some of it is easily interpreted or not. Challenging gender performance is a big part of my personal life and I have not seen it represented enough in Albanian art and in Albanian artists so, I wanted to contribute and play my part. I find gender expression as a form of art, and I would like people to see its relevance.

Kristi: How would you define gender?

Ema: Honestly, gender is such a fluid and personal topic that I feel it is difficult for me to give a concrete definition of it. Sure, for some people gender is the social construct of masculine and feminine features based on primal roles, but for others, gender is not as important. Personally, I do believe that gender is a social construct and personal to the individual, not at all limited or defined by sex. Gender is a state of being, that is neither concrete, nor stable, and especially not binary. It can be expressed in several different ways, not limited to physical appearance. While gender is about the person, it nevertheless does not define, nor limit the person.

Kristi: I have recently re-read an old essay of Judith Butler one of the most influential theorists of gender and queer theory, and I wanted to share that with you to start a conversation if you are OK with that. They defines gender as performative. But they (please notice how in Albanian we do not have a gender neutral pronoun to use for Butler) also warn us that “gender being performative” is quite different from “performing gender” (like in a theatrical performance) in the sense that “being performative” goes with some intentionality. Trying to make it short: “Performing gender” means that the gendered self comes prior to the act, but gender being performative means that in fact there is no gender at all, we simply constitute it by performing it. It is then entrenched in us mainly through endless repetitions throughout history to create the illusion of a core gender identity that is born with us. Where do you stand in this discussion? Do you agree with this interesting thesis that gender is not only constructed but in reality there might not be an objective thing such gender?

Ema: I agree with Judith Butler that gender is performative and thus gender expression is the person rather than a definition, but I am still not sure whether I believe gender does not exist at all. It is definitely subjective and varies strongly on the individual, as well as it is non binary and not determined by sex in any way, but I would say that gender has such a significant and real impact on human lives, whether that is the roles that it presents to an individual at birth, or the roles that will affect them later. Gender is a significant right as one is brought to life, because factors of it are forced on us depending on sex due to the heteronormativity of the general public, and factors of it are learned and depend on culture. So yes, I do believe gender is subjective and constructed, but it is real due to the very concrete and significant impact it has on people since birth and later in life.

Kristi: Have you thought about the future? What place does art holds on it?

Ema: I am still exploring my future. I definitely want to pursue something related to art. I have especially taken interest on videogame art and design, because I believe it is a very modern and relevant way of storytelling that could potentially be used to bring more representation and communicate and spread messages.